Design Strategies that Create Sustainable Public Spaces

As one of mankind’s most critical environmental issues, the impacts of climate change are often felt most intensely at the local level. While the effects of excess heat and increasingly intense rain events can be daunting, there is rising recognition that recreational spaces, such as parks, can be part of the solution. By cleaning urban air, providing shade, and absorbing excess moisture, parks can ease the effects of climate change on the greater community.

More and more, the designers with Snyder & Associates are being asked to create sustainable projects that can mitigate the impacts produced by the changing climate. Listen in as Landscape Architects Tim West, PLA, Clay Schneckloth, PLA, and Andy Meessmann, PLA share the park and recreation design strategies they use to address climate change challenges.

Podcast Agenda

- Creating Multipurpose Spaces to Increase Resiliency (0:20)

- Incorporating Trees into Sustainable Designs (2:46)

- Custom Park Designs and Other Sustainable Options (4:59)

- Increasing Infiltration through Permeable Pavers (5:43)

- Adding Best Management Practices (BMP’s) to Park Design (7:34)

- Budgeting Constraints and Sustainable Design (10:16)

Tim West, PLA, LEED®AP

Development Business Unit LeaderTim West, PLA, LEED®AP

Development Business Unit LeaderMaster Planning, Project Management, Athletic Design, Park Design, Public Engagement

Clay Schneckloth, PLA

Landscape ArchitectClay Schneckloth, PLA

Landscape ArchitectParks and Recreation Design, Sports Fields Design, Green Infrastructure and Native Plantings, Landscape Design

Andrew Meessmann, PLA

Landscape ArchitectAndrew Meessmann, PLA

Landscape ArchitectMaster Planning, Industrial and Commercial Site Design, Residential Development

Creating Multipurpose Spaces to Increase Resiliency

Tim West (0:20)

If I were to pick a word to describe climate change and its effect on what we do in the world of landscape architecture, I’d say intensity. There are a number of extreme rain events that have been occurring—a lot of warm winters with little to no snow. Then we have another year that might be bitterly cold, or we have frosts that extend into the ground over four feet. That extreme weather and the intensity of that weather is really having a rough go on plants. It’s hard on landscape materials, and it’s really changing the way we look at our design work.

Andy Meessmann (0:55)

I’ve been working as a landscape architect for over a decade now, and something that I’ve seen kind of flushed out is the integration of our discipline with the whole spectrum of design. As landscape architects, we have to bring together a lot of different professions in order to create a park or an urban plaza that’s more resilient, and that is able to plan for the effects of climate change.

I think as landscape architects, we often lead these projects, and we really have to understand how to unite all these professions that come together to ensure that a design is sustainable, usable, and, most importantly, buildable. We have to know a little about a lot in terms of the architecture that goes into some of these places. The site planning, ecology, civil engineering, horticulture, and finally the construction and how all these pieces must be woven together to fight climate change, to help reduce the carbon pollution, the heat island effect, and localized flooding that happens in some of these spaces that we work in.

Clay Schneckloth (1:56)

I agree with what you’re saying there. With a lot of our projects that we’re working on, they start to include some additional parking for the facilities that we’re providing at these parks. And when we’re working with the cities, we’re seeing more requirements of some islands to help with that heat island effect.

Andy Meessmann (2:15)

Yeah. I also see it too. Working with cities and downtown districts on some of these smaller parks and urban plazas, we have to create multipurpose spaces now for planting beds that can absorb water, that provides a little bit more coverage for plant root systems and also places that some of these cities that we work with still need to dump snow into and pinpoint plants and material that’s going to withstand the salt, the additional snow loads and frequent rain events that happen in these spaces.

Incorporating Trees into Sustainable Designs

Tim West (2:46)

We’re also working on some projects in downtown Des Moines that address different ways to treat street trees, and there’s a pilot project going on where we’re actually lowering the tree pits along the roadway and incorporating some of the stormwater flows into the tree planters. We incorporated some drain tile and some rock riprap through that, so it can overflow and take the water away after it infiltrates through there. It also is siphoning off some nutrients and some of the water that the tree might need in a smaller tree pit area and be able to get them healthier growth and see if that’s going to work. I think there are a lot of different things that we’re trying to incorporate into our designs that really have a positive effect on how healthy plantings are and how they can be used in a better way to accommodate some of these different types of aspects of climate change or intensity.

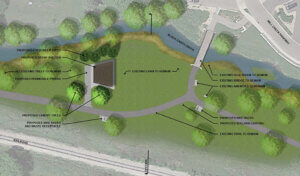

The Terra Lake project transformed a decommissioned sanitary sewage lagoon into an eight-acre lake and community park with multiple connections to a regional trail network.

Another area we’ve seen a lot of interest is in providing shade. Andy had mentioned a little bit about the heat island effect and how we want to reduce that. A lot of our playground work, the bigger component that’s usually requested is not necessarily cooler or the newest playground type of design, but more shade and incorporating places for people to sit and get out of the heat when they’re utilizing the playground in the summertime.

At Terra Lake in Johnston, we incorporated a number of canopies. These were little areas that were associated with the playground pads themselves on the elevated platforms with some leaf-like elements that shaded those parts of the playground, as well as a couple of shelters. So people could get in and out of that intense heat and sun and have a more enjoyable experience.

Clay Schneckloth (4:33)

Even in some of these newer parks, where we might not have the tree canopy, we’re getting the same request to provide some of these shade structures. So even if it’s just at a single bench, there’s been a request to be able to provide a shade structure to be able to get out of the sun there. Even some smaller picnic shelters, rather than just a large mass of shelter, we’re seeing some requests for some smaller picnic shelters with shade.

Custom Park Designs and Other Sustainable Options

Andy Meessmann (4:59)

The fun part about being a landscape architect is when you get a request for more shade on a playground, which makes a lot of sense. The fun part is to come up with a custom design that can cater to that request. It might be in terms of how you theme a project. If you have a homesteading theme on a certain playground, think about those unique features like a covered wagon, an old barn, a silo, or something like that where you can easily customize shade structures that take on a theme in a park. It’s a fun way that we express our designs in terms of creating a fun space for kids to play in, but allowing that shade component to also integrate into the design and fulfill the client’s request.

Increasing Infiltration through Permeable Pavers

Tim West (5:43)

We’ve incorporated permeable pavers in a lot of our projects. A couple of them have been in park projects where we wanted to encourage infiltration into the subsoils. There’s been kind of a differing approach to the color of those pavers, in the places where we’ve used darker colored pavers, those areas melt quicker. They tend to hold less ice in the wintertime. The lighter pavers tend to be better on the reflectivity. So you have to take into account what your site conditions are, but for the most part, we try to choose lighter paver materials, so they don’t hold as much of the heat.

Andy Meessmann (6:25)

That leads into the conversation of infiltration, and the whole idea behind permeable pavers is to get that water to filter through in a more natural process instead of just dumping it directly into a lake or stream body. Something we deal with quite a bit in Wisconsin and Iowa is the infiltration rates and how we deal with the larger context of where we’re putting this water and the green space that’s required for it. We see it more in our urban projects and our development projects for some of the private development that we work on. The big thing is to educate the client on the rationale of why you might need a bioretention basin or infiltration basin and ways to make it look good. A lot of times, maintenance issues pop up, and there are a lot of challenges with them, but a lot of these infiltration basins and bioretention ponds could look really good, in particular in larger park settings where you can bring in the user to help them understand what’s happening in these spaces. It could be an interesting approach to help captivate some of that leftover space and make it more of an amenity.

Adding Best Management Practices (BMP’s) to Park Design

Tim West (7:34)

One thing that we’ve really tried to do in our design work is to have multiple stormwater features within a park. So that there’s a little bit of an educational aspect to that design, so people can see why we’re putting stormwater in a particular area and why it’s important to put that back into the groundwater system and not necessarily let it run over land to different areas in the site. A lot of times, we’ll try to run any parking lots or large trail or plaza areas that are in a park into some sort of a stormwater management area or use a best management practice, which is also abbreviated as BMP. These BMPs can be anything from the infiltration basins and the bioretention areas that Andy described or the permeable pavers that we use on some of our projects. It’s really important to make sure we’re capturing and cleaning that water before it gets into a stream, creek, or nearby pond.

Usually, the parks and sites that we work in have some sort of a hydraulic aspect to them whether it’s to convey drainage through some backyards and a small park that might be associated with a development or something large like that Terra Lake project where we built a pond and are trying to maintain the quality of the water in that pond so it can perform as an urban fishery.

Clay Schneckloth (8:59)

Communities do not have to be large to incorporate BMPs. It can be a test plot or a test spot within your park system. A number of years ago, we worked with the City of Ames on a park on the north side by Ada Hayden, called Charles Calhoun Park. It was a small parking lot that was going to provide access to Ada Hayden and the trail system, and we used this as a test area. We divided the parking lot into two areas, one half drained to porous asphalt, and the other half drained to bioretention. Then we did some monitoring over the years to determine options on maintenance and options on what would you do differently if you were to install it again. Then from that point, I think they’ve made some decisions and moved forward with a couple of different options with their future parking lots and what they’d like to see.

Another option that we’ve talked about before and have incorporated into many projects is using stormwater detentions and recycling that water for an irrigation system. Practice fields east of Jack Trice Stadium at Iowa State, we created a stormwater detention basin that they were going to use for irrigating their practice fields. So that’s another option.

Budgeting Constraints and Sustainable Design

Tim West (10:16)

With specific design plans, clients are able to understand what their space will look like and what elements they can include in their budgets.

As we’ve talked about incorporating a number of these new technologies or new aspects to park design, what comes to mind is there are a lot of different potential maintenance changes that come along with that. Are you guys seeing a lot of changes based on these new amenities, or are there other things that are driving park maintenance changes when we start looking at environmental impacts?

Clay Schneckloth (10:42)

An item that I hear about most is the budget. The parks directors only have so much money. They’re all trying to expand and create better park facilities for their community, but their budgets are holding them back sometimes. They’re looking at ways how can they still achieve this great park system with the budget they have. We’re looking into what are you doing for mowing? Do we need to mow this entire area that you have in this park system? Are there different options rather than just a mown turf that we can incorporate into this area?

Tim West (11:16)

By not having all that mown, you might be able to utilize native plants or other types of plant areas to promote more stormwater infiltration.

Another place that we’ve seen some reduction to turf maintenance is the conversion of real turf to fake turf and it happens a lot more frequently than you might think in the municipal parks. We see it a lot in athletics, but we’re starting to incorporate synthetic turf into different types of parks and multi-recreational areas.

In Altoona, we worked on the Spring Creek Soccer Complex and although they have a number of practice to competition level fields of varying sizes, they wanted to incorporate a synthetic turf system so that they could still have events when they have frequent flooding or frequent rainfall. They can also change the maintenance for that area. That competition field that might see more use, they don’t have to mow it and maintain it, setting aside that field for regrowth. So it really starts to make sense when you have some intense activity in a particular area. A synthetic surface might be the right choice.

Tim West (12:36)

Well, I’d like to thank Andy and Clay for participating in today’s podcast and the great discussion that came through on how we continue to adapt our design work to address climate change.