Adding More Lanes to a Road is Not Always the Best Solution

Whether you drive, bike, walk, or use public transit, safety on our nation’s roadways is critical. In the 1950s and 1960s, roadway projects almost exclusively focused on system and capacity expansion. When the traffic volume of a two-lane road exceeded what it could accommodate, more lanes were added. This was a typical solution to address congestion issues, so four-lane roads became the norm across the country. But more lanes are not always the best solution for every corridor.

“Four-lane, undivided roadways often operate like two-lane ones with left-turn lanes. People often shy away from using inside lanes because of the waiting potential caused by left-turning drivers,” explains Tony Boes, PE, PTOE, Principal Traffic Engineer for Snyder & Associates. “Inside lanes become de facto left-turn lanes.”

Road Diets Quickly Becoming Commonplace Solutions

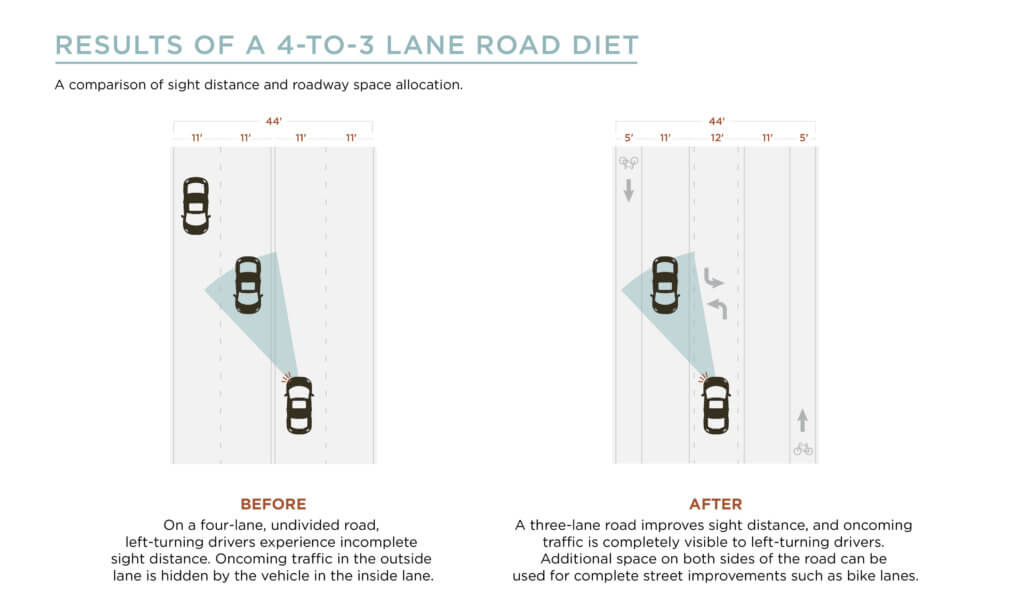

A “road diet” refers to removing vehicle travel lanes while maintaining the same width. The most common form of a road diet (lane reduction or lane reconfiguration) converts a four-lane, undivided road into a two-lane road with a center, two-way left-turn lane. Here’s how that looks in reality.

“Road diets change how roadway space is allocated. It uses the same amount of pavement but moves the stripes around,” adds Snyder & Associates Traffic Group Leader Mark Perington, P.E., PTOE. “By giving left-turning traffic its own space and through traffic its own space, you only need three lanes, not four. The extra space created by a road diet can be used for parking spots, bike lanes, and other complete street improvements that encourage active transportation and support the local economy.”

Numerous Benefits of the Road Diet Solution

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) reports that four-lane, undivided roads have a history of high crash rates. For roads where collisions and speeding are expected or in sensitive areas near schools, parks, and neighborhoods, lane reductions provide significant benefits, including an overall crash reduction rate of 19 to 47 percent. They also experience a reduced likelihood of rear-end and left-turn crashes with the addition of a dedicated left-turn lane.

A lane reduction strategy also means fewer lanes for side-street motorists to cross, reducing the rate of right-angle crashes. Likewise, pedestrian safety increases exponentially with fewer lanes to cross. Dedicated bicyclist/pedestrian space also helps to increase driver awareness of other roadway users. Plus, designated bike lanes, on-street parking, pedestrian refuge islands, and transit stops are possible through reallocation of space.

A road diet also “calms” traffic and reduces vehicle speeds, which helps reduce crash risk and the severity of collisions. The turning gap selection for left turns is simplified, with only one lane of traffic to cross. This is especially important for inexperienced and older drivers as these age groups experience higher rates of traffic crashes. The wider shoulders created by a lane reduction offer recovery space if a driver departs the road. This area also allows buses, mail vehicles, or delivery trucks to pull out of traffic so cars can pass.

As a further bonus, increased economic vitality often accompanies lane reduction projects, creating a destination for users. People are more likely to explore and enjoy the area when on-street parking, walking areas, and bicycle lanes are available.

“The number one benefit of a road diet, however, is safety,” says Boes. “By reducing the number of lanes, you don’t have through traffic mixing with turning traffic as much. As a result, we often see a significant reduction in rear-end, side-swipe, and left-turn crashes.”

Expert Advice for Making a Road Diet Feasibility Determination

Even though road diets increase safety and help foster a cohesive transportation network, they aren’t appropriate or feasible in all instances. “A road diet isn’t an automatic, one-size-fits-all solution,” states Perington. “From the number of driveways and intersections in a corridor to right-of-way availability and cost, there are many factors to consider before moving forward with a road diet.” When evaluating a corridor, understanding your community’s goals for improvement is helpful. Common objectives include:

- Improving safety

- Reducing speed

- Mitigating queues associated with left-turning traffic

- Improving the pedestrian environment

- Improving bicyclist accessibility

- Enhancing transit stops

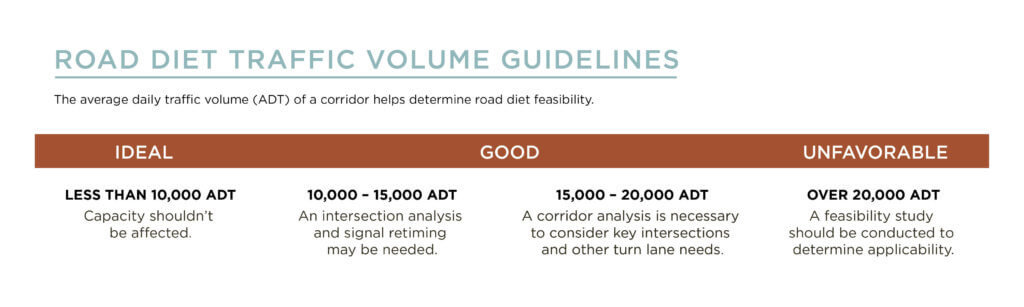

“To determine road diet feasibility, we begin by looking at the existing traffic volume and crash history of the corridor,” explains Boes. “We may also recommend a detailed analysis of existing conditions to see what’s working and not working while considering the area’s growth potential.”

Road Diets Offer an Economical Solution

As funding for roadway projects becomes increasingly limited, the desire for cost-effective, intelligent solutions is stronger than ever. The primary expense associated with road diets is road signage, lane markings, or signal modifications, so they’re relatively inexpensive. They can be planned in conjunction with other maintenance efforts, like resurfacing. In addition, road diets occur within the existing roadway footprint. This may reduce or eliminate costs associated with large reconstruction projects.

Federal funding for road diets includes the Surface Transportation Program or Block Grant (STP/STBG) and the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP). Where crash data support the expenditure, other state-level DOT traffic safety programs may also provide funding. “Unless you have to improve existing pavement, there’s typically no pavement construction cost, which can save a significant amount of money on transportation projects,” says Boes.

Education & Public Outreach Guide Road Diet Implementation

According to the FHWA’s Road Diet Informational Guide, road diets have become more common since the 1990s, with some of the first installations occurring in Iowa, Minnesota, and Montana. The Snyder & Associates traffic and transportation teams were at the forefront of road diet implementation in Iowa and have continued to assist communities ever since. While lane reductions are becoming more common and research shows significant benefits, they remain controversial for some communities.

“It can be difficult for the public to see the value of a road diet and how reducing the number of lanes will improve safety without causing an excessive delay in their community,” says Perington. “During public engagement, we must put ourselves in their shoes because the concept is counterintuitive. In addressing public concerns, we can share data and provide examples of where road diets have worked. Their opinions usually change once the implementation is complete and people see it working.”

Snyder & Associates Road Diet Experience

Fifth Avenue South in Fort Dodge and Lincoln Street/Iowa Highway 14 in Knoxville are two road diet projects Snyder & Associates recently completed.

Before converting 5th Avenue South to a three-lane roadway, it was a four-lane facility where speeding was common and the crash rate was higher than average. When the conversion was proposed to the public, opposition was built from local businesses and citizens. Snyder & Associates worked with the city to educate the public on the benefits of the conversion. The city ultimately moved forward with the lane reduction project. Since completion, speeds have dropped significantly through the corridor, and the number of crashes has been reduced.

“In the City of Knoxville, we recently assisted the city and Iowa DOT with road diet concepts and funding applications,” Boes says. “The road (Lincoln Street/Iowa Highway 14) needed repair, so rather than resurfacing it and putting it back the way it was, the city opted to explore options to improve safety progressively. Collisions involving left turns in that area were fairly common. The city maximized its investment by doing a road diet in conjunction with resurfacing and created a safer, more efficient corridor.”

As Perington reflects on his experience, he’s optimistic about the future of road diets and looks forward to helping more communities make their streets safer. “Our (road diet) experience dates back to the early 90s, so we’re well-prepared to help assess feasibility, model operations, and address public concerns common with road diet conversion projects. Safety is paramount, and a road diet may not always be the best solution. When it’s not, we’ll help you determine the right fit.”