Biosolids Management

Treating community wastewater is a requirement for the safety of public health and the environment. Biosolids are nutrient-rich organic materials that result from the wastewater treatment process. There are several options to dispose of this solid residue for biosolids management, including incineration, landfilling, or other forms of surface disposal. After treatment and processing, biosolids can also be recycled and then applied as fertilizer to create a safe and beneficial agricultural product.

While farmers and gardeners alike have used recycled biosolids to reduce the need for chemical fertilizers for decades, biosolids must be treated and tested to meet strict federal and state requirements prior to application. During this webinar, Patrick Williams, a wastewater engineer with Snyder & Associates, reviews details on the laws and specifications for the land application of biosolids. Williams also explains the specific obligations and steps for the wastewater facility operators to comply with the reporting and recordkeeping regulations of land applying biosolids.

Webinar Agenda

- Introduction (0:17)

- What are Biosolids? (1:01)

- Biosolids History (1:25)

- Biosolids Incineration (3:09)

- Landfill Biosolids Disposal (4:21)

- Biosolids Classification (5:42)

- Heavy Metals (8:37)

- Vector Attraction Reduction (10:00)

- Biosolids Land Application (11:15)

- Biosolids Uses and Laws (11:56)

- Biosolids Reporting and Recordkeeping (15:53)

- Net: NPDES eReporting Tool (17:45)

- Supplemental Information (18:20)

- Biosolid Land Application Five Year Plan (18:41)

- Dewatering Sewage Sludge for Biosolid Land Application (20:16)

What are Biosolids? (00:17)

My name is Patrick Williams. I am a civil engineer at Snyder and Associates in Cedar Rapids. During my time at Snyder and Associates, I’ve worked on a lot of different projects from wastewater treatment plants, drinking water treatment plants, large-diameter sanitary sewers, and water main distribution systems. One of the more interesting aspects of my job has been helping operators with their biosolids management reports they have to submit every year. The purpose of my presentation today is hopefully getting everybody a little bit more familiar with some of the regulations with biosolids and land application. So helping out with operators in the report, I noticed that a lot of people didn’t have the full view of what all the laws and regulations were with biosolids and land application. So the purpose of this report is to help everybody get more familiar with those. Biosolids are essentially human waste that we repurpose to help plants grow. It’s a fertilizer. They come from wastewater treatment plants. When wastewater enters a wastewater treatment plant, it is processed. And through those pipes, there’s a lot of different types. Solids are generated, and we can repurpose those it’s called sewage sludge or biosolids. We can repurpose that in many different ways.

Biosolids History (1:25)

I want to go into a little bit of the history of why bio-solids are heavily regulated. In 1973, the EPA established the Clean Water Act. The Clean Water Act established the basic structure for regulating pollutant discharges into the Waters of the United States. From there, in 1988, the dumping ban act was established, which banned all wastewater disposal of biosolids into the ocean. After this point, you can no longer dump your biosolids into the ocean, and you could either land apply it or landfill the biosolids. In 1993 they amended the Clean Water Act and established section 405 permits, it’s for sludge management, and that set the groundwork for regulating sewage sludge.

Soon after that, the part 503 rule, which is the standards use of disposal of sewage sludge, that’s basically the entire federal law of how sewage sludge has to be regulated. If you do manage a sewage sludge wastewater plant, I highly recommend familiarizing yourself with this rule because it’s very important to know what you can and cannot do. So in 2016, they recorded 7.1 million dry tons of sewage sludge being used or disposed of annually in the United States alone, and 47% of that was land.

When I started my career as a civil attorney engineer, they established the Net: NPDES eReporting tool. I know everybody’s not a fan of that, and they’re used to the paper copies, but when I started, that’s all I was familiar with. So I’ve helped operators work through the Net: NPDES eReporting tool and help them get their reports correctly. After the second year, it was established 96.5% of all biosolids reports were submitted electronically.

Biosolids Incineration (3:09)

The three main disposal options for sewage sludge are incineration, land application, and landfilling. And I’m going to go through all three, but primarily I’m going to talk about the land application of biosolids. Still, I just want everyone to be familiar that there are other options available to dispose of your sewage sludge. The first method for disposal of sewage sludge I’m gonna talk about is incineration. Incineration is basically flaming up your biosolids and turning them into ash. It takes place in two steps. First, you need to dry the solids to about 15 to 35% solids, and then you can combust them, which will delete about 65 to 75% of the volume of the sludge, which contains the volatile part of the matter. Since the volume of the ash is significantly lower than the original product, it’s very cheap to transport and landfill ash, but you don’t have to dispose of the ash in a landfill.There ares also a few other options that you can use:

The three main disposal options for sewage sludge are incineration, land application, and landfilling. And I’m going to go through all three, but primarily I’m going to talk about the land application of biosolids. Still, I just want everyone to be familiar that there are other options available to dispose of your sewage sludge. The first method for disposal of sewage sludge I’m gonna talk about is incineration. Incineration is basically flaming up your biosolids and turning them into ash. It takes place in two steps. First, you need to dry the solids to about 15 to 35% solids, and then you can combust them, which will delete about 65 to 75% of the volume of the sludge, which contains the volatile part of the matter. Since the volume of the ash is significantly lower than the original product, it’s very cheap to transport and landfill ash, but you don’t have to dispose of the ash in a landfill.There ares also a few other options that you can use:

- filler in cement and brick manufacturing,

- base material in road construction,

- daily landfill cover, but you need to pelletize the ash first,

- filler in athletic facilities, such as baseball, diamonds, arenas, and racetracks.

Landfill Biosolids Disposal (4:21)

There are two types of landfills that you can dispose-in. One is called monofills, which is a sewage sludge-only landfill. I’ve never actually heard of monofill before I started researching this, so they’re pretty rare. They’re also very heavily regulated by the EPA. Since it is heavily regulated, there are a lot of rules that you must follow. If you’re going to dispose in a landfill, you need to have a liner on the bottom of the landfill, and you need to follow an entire subsection of the 503 rule to make sure that it’s not polluting any of the environment.

Biosolids disposed of in monofills need to meet Class A and Class B pathogen requirements. The different types of monofills could be a trench system, an area fill system, or a similar bulk disposal operation. It usually involves a cover system material deposited over the sewage sludge. So the second type of landfill you can dispose your sewage sludge in is a co disposal landfill. This is a combined biosolid and municipal solid waste landfill. This is a lot more common, and there’s hardly any regulations for it. I know landfills aren’t super happy to have biosolids deposited in their landfills, but it is a legal option that you can take. Just another note, if you use your biosolids is cover for a landfill at the end of the day, that’s not considered landfilling. It’s considered land application. So the rules of land application follow that part of landfilling.

Biosolids Classification (5:42)

There are three major types of classification that EPA and DNR go by pathogens, heavy metals, and vector attraction reduction. Pathogens are disease-causing microorganisms. There are countless types of microorganisms out there, and it’d be very, very expensive to test for every single one to make sure your biosolids sample didn’t have any in them. That’s why they test for indicator organisms. Instead, indicator organisms are either fecal Coliforms, Salmonella or E-coli and they represent the probable presence of pathogens in the sample. So we test for those. And if there’s a lot of Fecal Coliforms, a lot of Salmonella, there’s a high chance that your biosolids could get somebody sick.

Class A Biosolids

There are two different ways that the EPA and the DNR classify biosolids by pathogens, Class A and Class B. Class A is the best type of pathogen densities that you could have and have your biosolids classified as Class A that you cannot have any detectable limits of indicator organisms in your biosolids. If you’re selling biosolids that are considered a Class A, you have to test the biosolids at the time of sale to make sure that you are not selling biosolids that contain high levels of pathogens. Also, you must meet several pre-treatment requirements. I’m going to go through those pretty quickly, but if your biosolids are treated thermally in a high pH environment, they can test for enteric viruses or Viable Helminth Ova. Enteric Viruses are viruses that are associated with human feces. Viable Helminth Ova, does anybody know what that is? Helminth means parasitic worms, and ova means eggs. So if you have parasitic worm eggs in your biosolids, then you can’t classify those as Class A biosolids.

Other processes that you can use to have them considered Class A are composting heat drying, heat treatment, thermophilic aerobic digestion, beta ray radiation, gamma-ray radiation, and pasteurization. And those are usually pretty expensive methods. So that’s why not a lot of operators choose to treat their biosolids to get the Class A designation, but those are options that you can take if you want to have a higher cost of sale of your biosolids.

Class B Biosolids

The second class of biosolids based on pathogens is Class B biosolids. These do not require time-of-use testing, but you still need to make sure you test for pathogens based on how many pounds of biosolids that you generate. There are some restrictions and bio cells, which I’ll get into later with Class B, but basically, those restrictions are on crop, harvesting, animal grazing, and public access.

So if you treat a farm field with Class B biosolids, there are some heavy restrictions that you must follow or the person that plants must follow. And I’ll get into those a little later, but I’m going to move on to heavy metals, which is the second way we help classify biosolids.

Heavy Metals Classification (8:37)

Probably pretty hard to read, but these are the tables that show you the amount of heavy metal concentrations that you can have in your biosolids. And based on those, you can have your biosolids classified by the DNRs Class I or Class II. There are ten heavy metals in total. But I think there might be less for the DNR higher quality. Biosolids have stricter regulations on metals. And if you have regular biosolids, you just have to meet ceiling concentration limits. However, whether they’re high quality or normal quality, you still have to meet the cumulative and annual pollutant loading rates for the biosolids.

So you’ve got to make sure that you are taking good records of how many biosolids you’re applying to a field and how big the field is. Because if you apply more kilograms of a metal per acre, EPA finds out, then you could be liable to get into trouble. One of the things I want to highlight in this presentation is: record everything that you can because if you don’t have records in four years down the line, someone gets sick, and they find out that the field, someone got sick, had heavy metals or pathogens in it. And you can say, well, I did all this testing, and I applied according to the law, and you can’t be held liable, but if you have no records, you can easily be fined and possibly lose your license to practice wastewater operating. Make sure you test your biosolids the number of times that you are required to buy your permit.

Vector Attraction Reduction (10:00)

The final method we help classify biosolids with is vector attraction reduction. So in an ideal world, all of the biosolids generated would have zero pathogens, and nobody would get sick, and we could apply them everywhere, but that’s not always the case. So did deal with having pathogens, going into farm fields. We have to practice a vector attraction reduction to make sure that the risk of anybody getting sick from the fields is reduced. So what is a vector? It’s an organism such as an insect or an animal that can transmit a disease to a human. So flies cows, anything that can get their hands on the biosolids and make contact with the human could get somebody sick. That’s a vector, there are 12 total ways that you can accomplish vector attraction reduction, but you only need to do one of the 12.

The first category is biosolids processing, and there are nine options. The second option is physical barriers, and that can be done by injecting biosolids beneath the soil surface or mechanically incorporating by disking or covering the biosolids with dirt after you apply them. So as long as you have one of those physical methods or one of the nine biosolids processes, you’re good to go for vector attraction reduction.

Biosolids Land Application (11:15)

Land application of biosolids is pretty important. It’s a very environmentally friendly, as long as nobody gets sick, way of fertilizing soil. And there are a lot of things that go into land application on the legal side. That’s kind of what I want to just make sure everybody’s aware of those legal requirements before you just send your biosolids off without really knowing what the rules you need to follow are. So a quick summary of what I’m going to talk about: the land application uses, the laws associated with it, some disadvantages to land application, how you need to report your land application, some supplemental information you need to provide on your report to the EPA and DNR, and the five-year plan.

Land Application Uses & Laws (11:56)

So most people probably think of land application as farming and agriculture, but you can also use your biosolids to help with forestry or mine reclamation. I’m not sure the second two were very popular in the state of Iowa, but can also repurpose your biosolids as a landfill cover as well. So, the DNR classifies biosolids as Class I or Class II, when they both have different requirements associated with them, the class I bio-solids are the high-quality biosolids and there are fewer regulations, but you do have to do a time of sale testing and you need to provide an information sheet whoever’s receiving the sludge, containing the name and address of the sludge generator. A statement that application of the sewage sludge to the land is prohibited except in accordance with the instruction on the information sheet and your annual application rate for the sludge.

Class I Sludge

So I’m sure most of you probably don’t have class I sludge because the requirements are so strict. So, the Class II land application requirements are something that everyone should be aware of. Those are all outlined in chapter 67 of the Iowa administrative code, which is probably not the most exciting read, but it is important to know what those requirements are. I do want to highlight a couple of them, and if you’re not aware of those, you should try to read that code and understand what they are.

Class II Sludge

So, Class II land application requirements, you can’t apply those to a lawn or a home garden cannot apply it to a land affecting a threatened or an endangered species. You cannot apply to soils classified as sand or silt or to the top five feet of the soil. You can’t apply it to land with a slope higher than 9%. You can’t apply it within 200 feet of a waterway. The list goes on and on. There are a lot of requirements. And when I was helping out another operator and submitting a report to the EPA, I kept having them come back to me and say, well, you don’t have this, you don’t have this. You’re not meeting this. You can’t apply here. You can’t apply here. And I realized, okay, this is probably really important for everyone to understand that, you know, if the EPA finds that you’re applying to a land that can’t be applied to, they can hold you legally liable and either subject to you to fines, imprisonment or loss of your license. So if you are generating sludge, even if you give it to companies to handle all of your waste solids, you’re still held liable as a generator. So if they are practicing malpractice with the biosolids, then you are still held liable for what happens to anybody at the end of the day. So, just make sure that everything is held on records that can protect you in the future and make sure that you’re following everything to the T.

Class B Site Restrictions

Finally, I want to just go over some Class B site restrictions. Class B, as you remember, are the pathogens that can be detected in your biosolids. If you land apply, you have to restrict public access to the land for a year, unless there’s a low risk, which can be 30 days animals can’t graze on the land for 30 days. And if you have food with harvested crops that touch the biosolids, such as stuff below the land surface, and you mechanically incorporate, then you can’t harvest those crops for up to 20 months. So just make sure that that stuff is not happening when biosolid is on land because it does put the public at risk. Now I want to move on and talk about a little of the disadvantages. And I feel like I am talking a lot about the disadvantages because there are so many different ways you can get people sick, but just quickly, the disadvantages can be the odor. Biosolids don’t always have the best odor. There are ways to help mitigate that during treatment. You can pollute water if the land floods and there are biosolids on the ground. You can pull out streams or rivers. So there is that risk. That’s why they encourage mechanical incorporation or injection. So the biosolids aren’t swept away in a flood or a rain event, and you can also get people sick. And that’s one of the things that you can be held liable if people die and they find out biosolids did it, then they’re going to come back to who applied them. And the operator’s the one who’s held liable.

Biosolids Reporting & Recordkeeping (15:53)

The amount of sludge that your facility generates dictates the amount of times you need a monitor for heavy metals and pathogens. If you produce zero to 325 dry tons of solids, you only have to test once a year. When I think the most popular one is 325 to 1,680 dry tons, and you have to test four times a year from there. If you have more than that, it’s six times per year. And even more than that, it’s 12 times per year, once a month. So make sure you’re testing your biosolids your required amount of times. Just to make sure you have as many records as possible

Reporting this has to do with the EPA report that you’re required to submit every year if you land apply. The big thing that I kind of touched on before, but the statement that you have to sign every time you submit a report is I’m going to read it, “I certify under the penalty of law, that the class of sludge that I’m applying the requirements have been met. I’m aware that there are significant penalties for false certification, including the possibility of fine and imprisonment.” If you have somebody prepare your biosolids report, as I prepared for other people, or you have your company that can fill out your report for you at the end of the day, the operator is still the one that needs to sign the report. And that’s why it’s very important to review the entire report and make sure everything that is on the report is as accurate as possible because that statement is something that could get you in a lot of trouble in the future.

Other things you need to report along with just that very scary statement, you need to describe how you’re reducing pathogens at your plant. You got to describe how your vector attraction reduction methods are being met. If you’re land applying to farms, you’ve got to say exactly where those farms are, how much land, how much sludge is being applied. So there’s a lot of stuff that you need to, you know, make sure you have good records for.

NET: NPDES eReporting Tool (17:45)

The NPDES eReporting tool is the electronic tool that everyone is pretty much required to use these days to report their biosolids. I know they have about a three-hour tutorial video that you can watch to figure out how it works, or they have a guide. But if anybody has issues with that, there are people out there, such as engineers or companies, that can help you get through the technical stuff, just so you can fill out the report as you need to.

The report is due. I believe February 19th of every year. So just make sure you don’t miss that date, or someone’s going to call you. And if you’re not doing everything, you know, above grade, that puts you liable to more notice.

Supplemental Information (18:20)

Something else you need to provide, and I kind of touched on this as supplemental information that includes field maps, records of your application, how much loading of metals you are doing, and how you’re actually applying it. If you’re using any mechanical or incorporation or injection, just describe as much as you can because that’s going to help you out in the long run.

Biosolid Land Application Five Year Plan (18:41)

There is another thing that you need to have at your plant. And that’s your five-year plan for land application. This is something that everyone that applies biosolids for land application needs to have. I’ve worked with a wastewater treatment plant, and the EPA did an audit on them, and they didn’t have their five-year plan, and they definitely started asking a lot more questions after that. So if you just have it stuck on a shelf somewhere and you update it annually, have an engineer do that for you. You should be good.

Some of the requirements, though, for your five-year plan, you need to have an outline of your sewage sludge sampling techniques and procedures. So that’s when you send it to the lab, just to let them know that every quarter I’m sending it to the lab, and this is what they’re testing for. It’s pretty easy. You need to determine which lands you’re planning to apply to in the future. Just saying that these lands I’ll follow within, you know, Iowa and federal code, you need to identify any methods of treatment that you have. You need to identify the names and the owners, the lands that you’re applying to the operators that are going to be working with the biosolids on the overall schedule of when you’re planning to land, apply the types and capacities of the equipment required. It’s all spelled out pretty well in the Iowa biosolids land application field guide available online. That’s the 2011 edition. It’s about 20 pages. I mean, it’s pretty small, but it goes through everything your checklist needs to have. As long as you meet everything on the checklist, it’s a very important resource to have.

Dewatering Sewage Sludge for Biosolid Land Application (20:16)

I want it to go through different dewatering technologies. And the reason I want to go through dewatering is because it’s an economic benefit to dewater your sewage sludge when you land apply. Not only because it reduces the volume of biosolids, which saves on money, storage, and transportation, but it also creates a material that lets you compost. It has better material and better quality for the soil. So it’s pretty good to dewater your sludge.

If you’re incinerating it, dewatering saves you on incineration and also produces a material that’s good for composting. So with the watering, there are a lot more different technologies out there besides the five that I’m listing.

Centrifuge Dewatering

The first dewatering technology is a centrifuge. And I’m curious to know, does anybody have a centrifuge at their plant? I didn’t think so. Yeah, I haven’t heard of a single plant that has centrifuges in Iowa, but they’re actually pretty cool. They work a lot like a laundry machine. The bio-solids are fed in, and the coil in the middle spins really fast, and that separates the liquids from the solids. On one end, the solids are discharged, and on the other end, the liquids are discharged, and it produces a lot higher quality, higher solids material than a belt filter. They do have some advantages such as low operation and maintenance costs, outperforming dewatering capabilities of a belt filter press pretty small footprint requirements compared to their capacity. There’s also minimum operator attention when things are running well, and they’re also very easy to clean. I’ve heard belt filter presses aren’t the easiest things to clean.

Disadvantages, though. It does have high power consumption. You also need a lot of experience to make it run very well. It’s difficult to monitor how well you’re doing because it’s basically a metal tube, and you can’t see what’s coming in out until you’re all finished. So you really need to have a lot of experience before this thing will run well. Spare parts are expensive, and you need to have the manufacturer come and repair them. If there’s a serious break, startup and shutdown can take up to an hour.

Belt Filter Press Dewatering

The next one is the belt filter press, which I’ve seen a lot of in the state of Iowa. I think it’s the most popular mechanical dewatering out there just because it’s so simple to use basically a belt filter, press the water sludge by applying pressure between the belt and the discs, and that presses the water out and creates cake. That, on average, has 15-20% solid content.

Advantages to this, our staffing requirements are pretty low. Maintenance is relatively simple, and the wastewater operators can generally perform all maintenance. It starts up pretty quick compared to a centrifuge, and there’s less noise compared to a centrifuge. Disadvantages. Odors can be a problem, but those can be controlled by chemicals and ventilation. You do need a lot more operator attention. If the feed’s solids vary in solid concentration and organic matter, wastewater solids need to be screened to minimize the risk of sharp objects damaging the belt. Belt washing can be time-consuming. It’s got a pretty large footprint compared to the centrifuge. If you’re looking to buy new dewatering equipment, I think it is worth it to just go through all your options because it may be worth it to get a belt filter press. It may be worth it to get a centrifuge. You just have to look at those operational and capital costs.

Gravity Thickening Dewatering

The third method for dewatering is gravity thickening. Gravity thickening typically takes place in a large circular concrete tank with a conical bottom. Wastewater is fed through the influent pipe of the tank, and water is stored in the tank, and solids will slowly settle to the bottom. They have these metal scraper arms at the bottom, which will collect the sludge in the middle, and the sludge is discharged out through the bottom, and the water comes out through the top over a weir. It does have a very large footprint, and the solids contents are only about 4-6%. So not as good. But it’s an advantage because it’s really easy and simple to maintain, and there are very low operating costs compared to the central fuse or belt filter press.

Drying Beds Dewatering

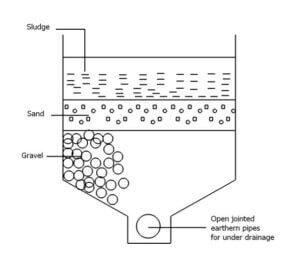

Drying beds are another pretty simple process for dewatering your sludge—three main different types of drying beds. Your conventional drying bed has a layer of sand and gravel and sludges fed through the top, and over time, the wastewater will percolate through the bottom or evaporate off the top. And after a few years, you’ll have a high solid product. You can get about 10% solids, which isn’t as good as the belt filter press or the centrifuge, but it does require very little maintenance once you get the solids on there. Since rain can be an issue, you can also put a glass or transparent fiberglass thing on top to prevent any water from getting in there, but that does restrict your evaporation potential.

Drying beds are another pretty simple process for dewatering your sludge—three main different types of drying beds. Your conventional drying bed has a layer of sand and gravel and sludges fed through the top, and over time, the wastewater will percolate through the bottom or evaporate off the top. And after a few years, you’ll have a high solid product. You can get about 10% solids, which isn’t as good as the belt filter press or the centrifuge, but it does require very little maintenance once you get the solids on there. Since rain can be an issue, you can also put a glass or transparent fiberglass thing on top to prevent any water from getting in there, but that does restrict your evaporation potential.

Paved and vacuum-assisted drawing beds aren’t as common. The advantage to the paved is you can drive equipment on it and the advantage to the vacuum assisted is you get a higher solid content because you have a vacuum at the bottom that sucks the water out a lot quicker than just normal percolation.

Reed Beds Dewatering

Reed beds are a pretty economical and environmentally friendly way to dewater your biosolids. Each basin needs to have a membrane filter sludge loading system, reject water, and an aeration system. The presence of the reeds provides mineralization to the organic salad and the sludge, regardless of the size of your plant. You really want to have a minimum of eight to 10 different reed beds. If you have too few basins, you run into operating problems such as poorly dewatered sludge residues and poor mineralization. And about every eight to 10 years is when you would empty these reed beds. The good thing about having reed beds is you can remove up to 25% of the organic matter, and he can produce biosolids with 20-40% solid content. It’s also very good because it’s very efficient at removing pathogens and taking away any hazardous organic compounds. And it also makes a very good option for recycling the biosolids for agricultural land application.

Patrick Williams, EI

Civil EngineerPatrick Williams, EI

Civil EngineerCombined Sewer Planning & Design, Hydrologic & Hydraulic Analysis, Water Main design